Anonymization

This is a type of de-identification where all sensitive data is removed. More details and a definition of anonymization are available in a previous blog post.

Code set

Also referred to as HL7® tables, vocabulary or code table. It is a list of codes and their meanings used to codify information included in HL7® messages. Codes could be defined by the HL7® standard itself or information systems.

For instance, here is the list of suggested values for patient gender as proposed by HL7® v2.6

| Code | Value |

| M | Male |

| F | Female |

| U | Unknown |

| A | Ambiguous |

| O | Other |

| N |

Not Applicable |

Component

The basic building block used to construct a data type. In the case of complex data types, each data element is a component.

Example: Patient Family Name (PID.5.1) is a component of Patient Name (PID.5)

Conformance Profile

A description of the data and messages that an interface sends and/or receives. Also known as an HL7® specification or profile. The description covers the data format, data semantics and acknowledgment responsibilities. The description must be clear and precise enough so that it can act as a set of requirements for data exchange.

Data Type

From the Health Level Seven International (HL7®) official site: “The basic building block used to construct or restrict the contents of a data field.” In other words, a data type will describe the format of field data elements (components). Example: Personal names are constructed using several pieces of information and should maintain the same structure across the board. The XPN data type describes such structure.

De-Identification

De-Identification occurs when all identifiers and quasi-identifiers (IDs, names, addresses, phone numbers, genders, etc.) are removed from the information set. This protects patient identity while most of the data remains available for sharing with other people/organizations, or for related uses. See our post on de-identification basics for more details.

ER7 encoding

This is a representation of an HL7® message using message, segment, field, component and sub-component delimiters. This encoding is usually referred to as a “pipe delimited” message.

Example:

EVN||200605290901||||200605290900

PID|||56782445^^^UAReg^PI||KLEINSAMPLE^BARRY^Q^JR||19620910|M||2028-9^^HL70005^RA99113^^XYZ|260 GOODWIN CREST DRIVE^^BIRMINGHAM^AL^35 209^^M~NICKELL’S PICKLES^10000 W 100TH AVE^BIRMINGHAM^AL^35200^^O |||||||0105I30001^^^99DEF^AN

PV1||I|W^389^1^UABH^^^^3||||12345^MORGAN^REX^J^^^MD^0010^UAMC^L||678 90^GRAINGER^LUCY^X^^^MD^0010^UAMC^L|MED|||||A0||13579^POTTER^SHERMAN ^T^^^MD^0010^UAMC^L|||||||||||||||||||||||||||200605290900

OBX|1|NM|^Body Height||1.80|m^Meter^ISO+|||||F

OBX|2|NM|^Body Weight||79|kg^Kilogram^ISO+|||||F AL1|1||^ASPIRIN DG1|1||786.50^CHEST PAIN, UNSPECIFIED^I9|||A

The other allowed encoding uses HL7-XML.

Field

According to Health Level Seven International (HL7®), a field is a string of characters. Fields for use within HL7® segments are defined by HL7®. A field is the basic building block used to construct a segment. By default, fields are delimited by the “|” character (see the above example) and are built with one or more components. Patient name (PID.5) is an example of a field.

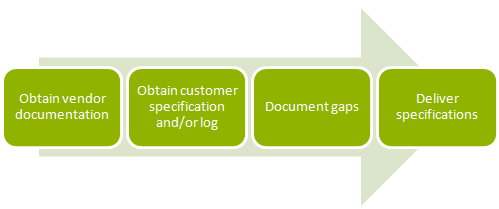

Gap Analysis

Gap analysis is the phase in a deployment project where analysts map the data elements between the product they are installing to the elements in the hospital’s existing information systems therefore detailing the gaps existing between the two sources. The result is usually a list of differences between data definitions. This list would then be used to configure/develop data transformation routines.

HL7®

HL7® is an international community of healthcare subject matter experts and information scientists collaborating to create standards for the exchange, management and integration of electronic healthcare information.

The name “Health Level-7” is a reference to the seventh layer of the ISO OSI Reference model, also known as the application layer.

Hospitals and other healthcare provider organizations typically maintain many different computer systems for everything from billing records to patient tracking. All of these systems should communicate with each other (or “interface”) when they receive new information but not all do so. HL7® specifies a number of flexible standards, guidelines, and methodologies by which various healthcare systems can communicate with each other. Such guidelines or data standards are a set of rules that allow information to be shared and processed in a uniform and consistent manner. These data standards are meant to allow healthcare organizations to easily share clinical information. Theoretically, this ability to exchange information should help to minimize the tendency for medical care to be geographically isolated and highly variable.

HL7-XML Encoding

This is a basic XML representation of an HL7® message where XML elements represent HL7® messages constructs like segments, fields and components. The other allowed encoding is ER7.

Example:

<MSH>

<MSH.1>|</MSH.1>

<MSH.2>^~\&</MSH.2>

<MSH.3>

<HD.1>MegaReg</HD.1>

</MSH.3>

<MSH.4>

<HD.1>XYZHospC</HD.1>

</MSH.4>

<MSH.5>

<HD.1>SuperOE</HD.1>

</MSH.5>

<MSH.6>

<HD.1>XYZImgCtr</HD.1>

</MSH.6>

<MSH.7>

<TS.1>20060529090131-0500</TS.1>

</MSH.7>

<MSH.8 />

<MSH.9>

<MSG.1>ADT</MSG.1>

<MSG.2>A01</MSG.2>

<MSG.3>ADT_A01</MSG.3>

</MSH.9>

<MSH.10>01052901</MSH.10>

<MSH.11>

<PT.1>P</PT.1>

</MSH.11>

<MSH.12>

<VID.1>2.5 </VID.1>

</MSH.12>

</MSH>

<EVN>

<EVN.1 />

<EVN.2>

<TS.1>200605290901</TS.1>

</EVN.2>

[…]

</EVN>

<PID>

[…]

</PID>

[…]

</ADT_A01>

HL7® v2.x Message

HL7® version 2 defines a series of electronic messages to support administrative, logistical, financial and clinical processes. The v2.x standards are backward compatible (e.g., a message based on version 2.3 will be understood by an application that supports version 2.6).

HL7® v2.x messages use a human-readable (ASCII), non-XML encoding syntax based on segments (lines) and one-character delimiters. Segments have composites (fields) separated by the composite delimiter. A composite can have sub-composites (subcomponents) separated by the sub-composite delimiter, and sub-composites can have sub-sub-composites (subcomponents) separated by the sub-sub-composite delimiter. The default delimiters are vertical bar or pipe (|) for the field separator, caret (^) for the component separator, and ampersand (&) for the subcomponent separator. The tilde (~) is the default repetition separator. The first field (composite) in each segment contains the 3-character segment name. Each segment of the message contains one specific category of information. Every message has MSH as its first segment, which includes a field that identifies the message type. The message type determines the expected segment names in the message. The segment names for a particular message type are specified by the segment grammar notation used in the HL7® standards.

Sample of a v2.2 message with customized segments:

EVN||200605290901||||200605290900

PID|||56782445^^^UAReg^PI||KLEINSAMPLE^BARRY^Q^JR||19620910|M||2028-9^^HL70005^RA99113^^XYZ|260 GOODWIN CREST DRIVE^^BIRMINGHAM^AL^35 209^^M~NICKELL’S PICKLES^10000 W 100TH AVE^BIRMINGHAM^AL^35200^^O |||||||0105I30001^^^99DEF^AN

PV1||I|W^389^1^UABH^^^^3||||12345^MORGAN ^REX^J^^^MD^0010^UAMC^L||678 90^GRAINGER^LUCY^X^^^MD^0010^UAMC^L|MED|||||A0||13579^POTTER^SHERMAN ^T^^^MD^0010^UAMC^L|||||||||||||||||||||||||||200605290900

OBX|1|NM|^Body Height||1.80|m^Meter^ISO+|||||F

OBX|2|NM|^Body Weight||79|kg^Kilogram^ISO+|||||F

AL1|1||^ASPIRIN DG1|1||786.50^CHEST PAIN, UNSPECIFIED^I9|||A

HL7® v3 Message

V3 is the latest version of the HL7® message standard. It is not backward compatible with the v2.x standard. Instead it implements a completely new top-down design approach based on the Reference Information Model (RIM) for better consistency and extensibility. HL7® v3 messages are XML documents exchanged between systems. Tags are defined through a suite of modeling mechanism. We see some adoption of this message standard around Clinical Document Architecture (CDA). However, most systems continue to exchange data using v2.x messages.

Integration Engine

An integration engine is middleware built specifically to connect systems by using a standard messaging protocol. The integration engine is responsible for mediating protocols, orchestrating message workflow, transforming message formats and guaranteeing message delivery.

Integration engines simplify system interoperability by allowing message feed management. In other words, you don’t need to manage system-to-system connections. Instead, messages are sent to the integration engine. Messages will be forwarded to any system meant to receive those messages using the protocol supported by the given system. If needed, transformation can be applied so a message is translated to the expected message format.

Interface

Hospitals and other healthcare provider organizations typically maintain many different computer systems for everything from billing records to patient tracking. All of these systems should communicate with each other (or "interface") when they receive new information but not all do so. HL7® specifies a number of flexible standards, guidelines, and methodologies by which various healthcare systems can communicate with each other. Such guidelines or data standards are a set of rules that allow information to be shared and processed in a uniform and consistent manner. These data standards are meant to allow healthcare organizations to easily share clinical information. Theoretically, this ability to exchange information should help to minimize the tendency for medical care to be geographically isolated and highly variable

Integration as a Service

Based on the SaaS model, this is a delivery model where a provider provides all required infrastructure to interface systems. Usually, instead of charging for licenses and hardware, the provider will charge per message.

Message

A message is the atomic unit of data transferred between systems. In the HL7® world, it comprises a group of segments in a defined sequence. Each message has a message type that defines its purpose. For example the ADT Message type is used to transmit portions of a patient's Patient Administration (ADT) data from one system to another. A three-character code contained within each message identifies its type.

Optionality

According to Health Level Seven International (HL7®), optionality refers to whether the field, segment or segment group is required, optional, or conditional in a segment.

Point to point

Direct integration between two systems where system A and system B directly exchange information without an intermediate system or middleware.

Pseudonymization

This is a type of de-identification. This process replaces data-element identifiers and quasi-identifiers with new data elements so that the relationship to the initial object is replaced by a completely new subject. After the substitution, it is no longer possible to associate the initial subject with the data set. In the context of healthcare information, we can “pseudonymize” patient information by replacing patient-identifying data with completely unrelated data. The result is a new patient profile or identity. The data continues to look complete and the data semantics (the meaning of the data) is preserved while patient information remains protected. Read more about pseudonymization in a previous post.

Repeatability

According to Health Level Seven International (HL7®), repeatability refers to whether the segment or field may repeat. The value set is the maximum number of allowed occurrences; if unspecified, there is only one occurrence, i.e., it cannot repeat.

Segment

A segment is a logical grouping of data fields. Segments of a message may be required or optional. They may occur only once in a message or they may be allowed to repeat. Each segment is given a name. For example, the ADT message may contain the following segments: Message Header (MSH), Event Type (EVN), Patient ID (PID), and Patient Visit (PV1).

Two or more segments may be organized as a logical unit called a segment group. A segment group may be required or optional and might or might not repeat. As of v 2.5, the first segment in a newly defined segment group will be required to help ensure that un-parsable messages will not be inadvertently defined. This required first segment is known as the anchor segment.

Sub-Component

The basic building block used to construct a component. In the case of complex data types using complex data type as components, each data element of the component is a sub-component. Example: Patient Own Surname (PID.5.1.1) is a sub-component of Patient Name (PID.5)

Trigger Event

Health Level Seven International (HL7®) defines a trigger event as “A real-world event creating the need for data to flow among systems. For example, the trigger event a patient is admitted may cause the need for data about that patient to be sent to a number of other systems. The trigger event, an observation (e.g., a CBC result) for a patient is available, may require that observation to be sent to a number of other systems. When the transfer of information is initiated by the application system that deals with the triggering event, the transaction is termed an unsolicited update.”

Read More in the HL7® Survival Guide

Introduction

Chapter 1: How to Integrate and Exchange Healthcare Data

Chapter 2: Pros and Cons of Interfacing Capabilities

Chapter 3: The Heart of the Matter: Data Formats, Workflows, and Meaning

Chapter 4: How to Work with Vendors and Developing Your EHR Strategy

Chapter 5: Vendors, Consultants, and HL7® Interface Specifications

Chapter 6: Interfacing Artifacts: HL7® Conformance Profiles or Interface Specifications

Chapter 7: Interfacing Artifacts: Gap Analysis

Chapter 8: Interfacing Artifacts: Test Scenarios and Test Systems

Chapter 9: Interfacing Artifacts: Message Samples and Test Messages

Chapter 10: Process and Workflow

Chapter 11: Maintenance, Troubleshooting, and Monitoring

Chapter 12: Definitions

Chapter 13: Contributors and Resources